Pride. It’s a month out of the year where we reflect what being LGBTQ+ means and how we can not only uplift this community, but everyone else. The LGBTQ+ community has accomplished so much over the years, yes, but there’s still so much ground to cover. Very Good Light is celebrating Pride Month through our very own Pride Week where we delve into diverse voices that push the boundaries of what being LGBTQ+ in 2018 means.

This year has been the proudest I’ve ever felt to be queer and Asian.

Everywhere I turn – nightlife, zines, Instagram, my local coffee shop – I see queer Asians flaunting their attitude, their platform heels, and a smoldering, IDGAF look that inspires me to be louder, prouder, and fearless.

But when I leave my New York City bubble, it’s a different story.

As queer Asian people in America, we only become legible in opposition to whiteness and straightness: News stories and social justice clickbait articles never simply uplift queer Asian identity. Instead, they frame us as victims: Racist sexual preferences excluding gay Asians are wrong; White supremacy tells us that Asians can’t be desirable, but they can! Look here!

SEE ALSO: Coming out as a queer Korean American was the hardest thing I had to do

We rarely see stories on queer Asian people talking about the first time they realized they were LGBTQ or the first hookup they had. Instead, we focus on the first time they experienced being fetishized by a white person, or the first time they saw “No Asians” listed on a dating profile.

API TransFusion: The journey to the historic retreat

"In 1987, I never could’ve imagined that I could really come out as a trans person."In the second episode of our new series, filmmaker Patrick G. Lee explores the journey to a historic retreat for Asian-Pacific Islander transmasculine people.

Posted by NBC Asian America on Wednesday, June 13, 2018

About a year ago, my mom asked my sister if I was gay. I sent my mom a letter, in Korean, to give her an answer. As I began to realize the full fallout from coming out, I committed to seeking out a queer and trans Asian American community here in New York.

Over the past year, I’ve learned what it feels like to be seen – seen by a community that rejects whiteness, straightness, and hypermasculinity as the baselines for desirability and success. I’ve come to realize that our work lies not only in pushing back against reductive stereotypes of queer Asian people, but also – and perhaps more importantly – in actively celebrating queer Asian beauty, brilliance, and history on our own terms.

Our community is already hard at work on this front. For this year’s Pride Month, I partnered with NBC Asian America to make a five-part docuseries on queer and trans API history.

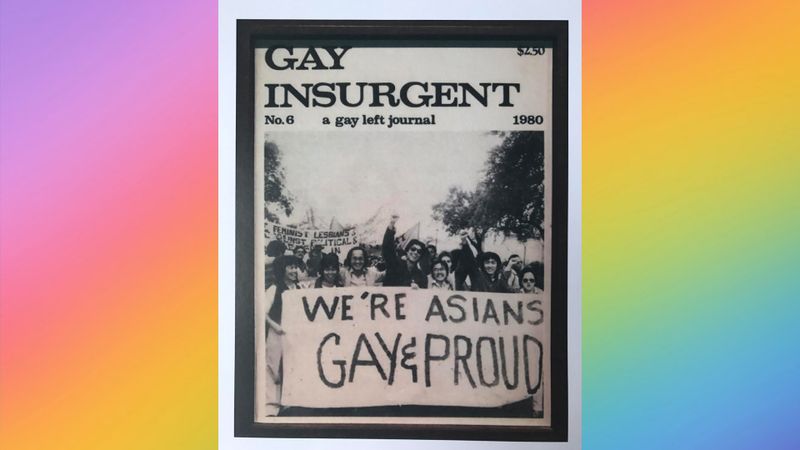

API Equality Northern California (APIENC) is home to an incredible archive of oral history interviews, called the Dragon Fruit Project, that documents “queer Asian Pacific Islanders and their experiences with love and activism in the 1960s, 70s, 80s, and 90s.” The project also helps create Wikipedia pages to document and disseminate our community’s histories.

Historian Amy Sueyoshi has published a deep-dive into queer Asian history entitled “Breathing Fire: Remembering Asian Pacific American Activism in Queer History.” And the Visiblity Project is a portrait and oral story archive led by photographer Mia Nakano that documents the Asian Pacific American women’s and transgender community.

Despite these efforts, editors and journalists still struggle to recognize that we as queer Asian people exist outside of the structures and systems that oppress us. They fail to see that our lives and our experiences have broader resonance – that we are not “super niche” or “exotic.”

As a filmmaker and journalist, I focus my storytelling on queer and trans Asian Pacific Islander communities. When I pitch story ideas to editors, the two most common reactions I get are either “No Asians” or “Not Asian Enough.”

“No Asians”

“This seems like a great idea, but can we broaden it? It’s too specific. We want it to appeal to more people.”

One of the first things I learned as a journalist is that the more specific you get, the more accessible your story becomes. We find power in hearing other people’s stories not because they fit the generic (a.k.a. whitewashed) and emotionally predictable arc of a typical Hollywood flick, but because there are specific moments of humanity that we can relate to and find resonance with.

Case in point: I grew up in the suburbs of Chicago on a diet of TV shows overflowing with straight white people, and yet I still found moments, characters, and storylines that nourished me, entertained me, and inspired me to become a storyteller in my own right. There’s no reason why we can’t and shouldn’t expect white audiences to do the same when they see a show full of people of color, or straight audiences when they see a movie driven by queer characters.

“Not Asian Enough”

“This is wonderful – but can we make this more Asian-specific? We really want to uplift some of the challenges that only queer Asian people face.”

This kind of comment almost always comes from a well-meaning editor whose quest it is to highlight the experiences of marginalized people. And yet, in undertaking a project whose aim is not to fetishize or orientalize “the other,” they end up doing just that, by seeking out trauma porn that is distinctly and undeniably different from the experience of whiteness or straightness.

And so, we can never have a queer Asian on screen talking about their career successes or their favorite gay bar. Instead, it’s always framed in terms of the struggles they must have endured to climb the ranks as a multiply marginalized person, or about the times they must have encountered blatant racism while just trying to enjoy a drink after work.

The gaze of white, heterosexist supremacy is forever lingering. And yes – that is incredibly important for us to recognize, name, and fight against. But especially during this month, Pride Month, I want to remind myself and my community that it’s OK to take a step back, block out the noise, and see ourselves at face value:

Powerful for being queer and Asian.

Sexy for owning all of who we are.

Unstoppable because we are here to stay.

READ MORE LIKE THIS