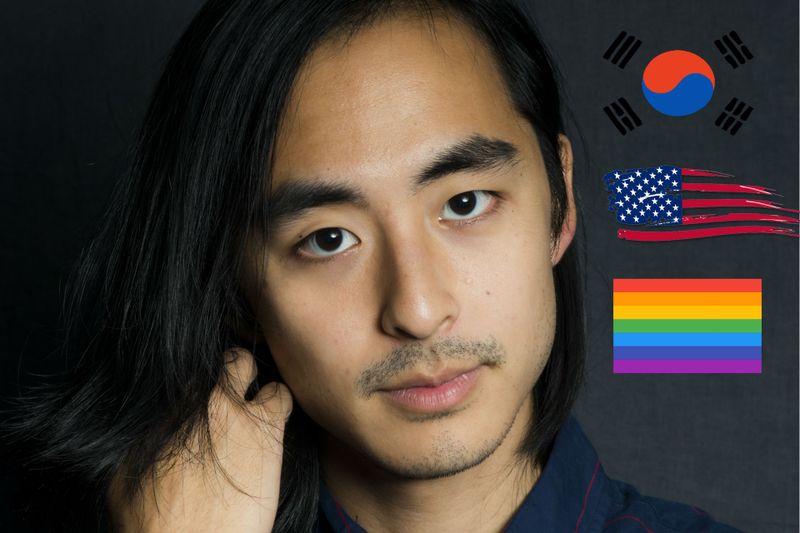

Before barbershops were cool and LGBTQ+ issues were being pushed forward, there was @rudysbarbershop. Since ‘93, this Seattle-based hub has been a proponent for inclusion, helping all people – straight, gay, bi and in between – express themselves through hair. 25 years, a product line, and many barbershops later, Rudy’s is still championing the cause of identity. True to their ‘For Everybody’ roots, Rudy’s supports partners like @itgetsbetterproject and @lalgbtcenter and donates shower products to shelters that serve LGBTQ+ youth.

I’m pretty sure Google Translate outed me.

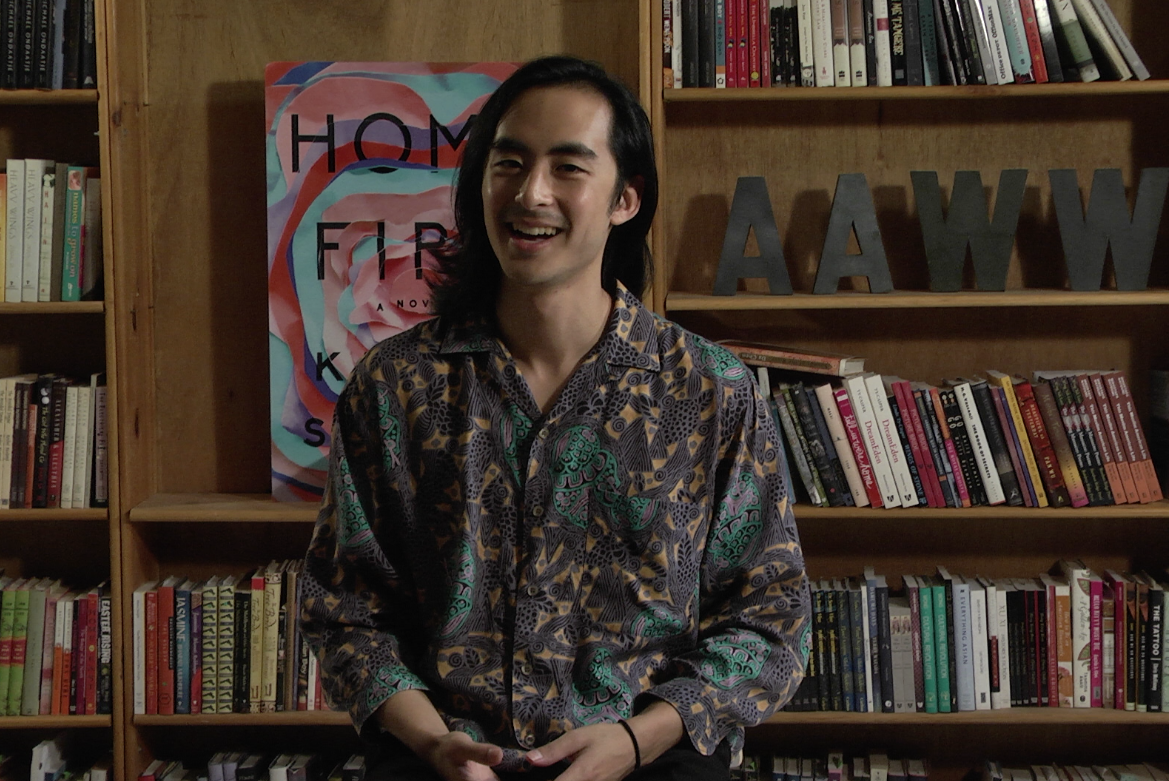

I had just finished marching in New York’s Pride Parade with my queer Korean drumming group. We marched down Fifth Avenue for hours, taking up space and making noise in ways that Asians in America are often expected not to do. It was an ecstatic experience.

Afterward, we took a sweaty group photo and I posted it on Instagram with the caption, “my badass queer Korean drumming family.”

Soon after that, my mom texted my sister a screenshot of the photo, asking her (in Korean), “Your brother’s not gay, is he?”

My sister then messaged me and asked, “What do you want me to say?”

My mom and dad moved to America in the 70s, and their English is pretty good. But “queer” is definitely a term they didn’t pick up during the decades they spent running their own business, making sure my sister and I were fed and shuttling us between after-school activities. So I didn’t think twice when I wrote that caption.

But, alas, technology. When you put “queer” into Google Translate, a Korean phrase comes up that literally means “same-sex love.” A pretty clear alarm bell for any parent, if you ask me.

And so began the process that I had avoided for years, and that I still hadn’t figured out a way to navigate. I felt a familiar tornado of anxiety churn in my stomach. I felt it every time I started thinking about what would happen if I came out as queer to my Korean immigrant parents. Would I still be able to visit home during the holidays? Would they try to come between my sister and me? Would they ever talk to me again?

Being a minority in America taught me to value my independence. It taught me to be self-sufficient, to be my own best advocate, to never settle for less. That’s actually how a lot of my white gay friends came out: They took a brave step toward full self-actualization, by choosing to put themselves first and to impose their truths on their family, so that they could be queer af and still go home for Thanksgiving.

I admired them for it. But it just wasn’t relevant to me.

“Your brother’s not gay, is he?”

My parents taught me about family duty. They taught me about swallowing down the pain to enable your kids and grandkids to live better than you did; about being halfway around the world from extended family; and about standing up for your dignity on a daily basis.

For us queer kids of immigrants, the feelings of guilt are real. The deeply entrenched sense of obligation is real. The exhausting toll all of this takes on our mental health is real.

Coming out is not just about us, as individuals; it’s about the repercussions that it might have within our immigrant communities and across generations of family spread across the globe. It’s about wanting to honor the sacrifices of our parents, who survived in a country that was not built for them and that continues to see them as foreigners, all so they could afford us more opportunities.

But in the moment that my sister messaged me, I did what came to me instinctively, as a journalist: I started writing.

I knew my Korean wasn’t good enough for me to communicate everything I needed to over the phone or in person. And I knew that if I came out in English, the power dynamic would be reversed, and my parents would feel helpless and lost.

And so I wrote a letter to my parents explaining what it meant for me to be gay. My hope was to fill in the gaps of their knowledge and push back against some of the opinions I knew they held after decades of going to a Korean Catholic church in my hometown just outside Chicago. I asked some friends — including Clara Yoon, a proud and affirming Korean mother of a bisexual, transgender son — to help translate the letter into Korean. Then I emailed it to my parents.

In that moment when I hit send, the knots in my stomach suddenly disappeared: I finally felt free. For the first time in my adult life, I had nothing to hide from my parents. I was fortunate enough to be financially independent from them. It felt less important to me how they reacted, and more urgent for me to get on with building my life.

Here’s a link to the letter I wrote.

My mom refused to read it. I think, in her gut, she knew what she would find inside, and she didn’t want to put herself through that. But it’s okay. I realize now that I wrote the letter mostly for myself, to affirm my own queerness: I wanted to find a tangible way to share more of who I was in Korean – a language and a culture that have always been my main point of connection to my family and to my ancestors, while at the same time being the biggest barrier in getting to know my parents and connecting with them emotionally.

I’m still figuring things out. Along the way, I’ve been documenting the stories of our community.

I found comfort in knowing that there were Korean words and phrases, references and metaphors, slang and idioms that could tell the story of what it means for me to be a queer Korean American. I feel affirmed by that language of queerness, even if it’s something my parents will never be able to fully embrace.

It’s only been a couple of months. I haven’t talked to my mom since I came out, but my dad seems to be taking it better. (He actually did read the letter.) I usually talk with him about once a week — random chit chat about the weather, about how work is going and, noticeably, an avoidance of the subject of whether I’m dating anyone at the moment.

Through it all, I will keep on drumming. I will keep marching, taking up space, shouting and standing up for my community, because that’s what we need to do to survive in a country where, at times, it feels like all the queers are white and all the Asians are straight.

I’m still figuring things out. Along the way, I’ve been documenting the stories of our community. On National Coming Out Day this year (Oct. 11), I’ll be releasing a short film about queer and trans Asians in America, asking them what they would say to their parents if they could speak the same language fluently.

To my extended, chosen family: You are not alone. There are queer and trans people who look like you, who speak 1.5 languages like you do, who feel stuck between two countries and cultures and are trying to figure out how being LGBTQ fits into all of that. There are immigrant parents who love their queer and trans children. And there is a community out there that loves all of who you are, unconditionally.

You are not alone.

RESOURCES:

The National Queer Asian Pacific Islander Alliance (NQAPIA) is a federation of nearly 50 LGBTQ Asian Pacific Islander groups around the U.S. You can poke around the website to find your local queer Asian group here: www.nqapia.org

NQAPIA hosts conferences, summits, leadership trainings, and healing spaces for us; and our local groups get together to share food and drink, to stand up for our queer immigrant community members, and to support one another as friends and chosen family.

There’s also a series of short videos and Q&A fact-sheets translated into more than a dozen Asian languages: http://www.nqapia.org/wpp/api-parents-who-love-their-lgbt-kids-multilingual-psa-campaign/

Here in New York, we have a PFLAG group specifically for Asian and Pacific Islander families. We have a monthly afternoon gathering for family members and LGBTQ people to gather and share stories, hug, drink tea, and laugh together.

https://www.facebook.com/apirainbowparents/

Reach out to any of these groups, even if they’re not near your home: Chances are, we’ll know of someone near you who can be a resource by phone, via Facebook, or by e-mail.

Finally, for the LGBTQ Koreans out there: We’re currently planning the inaugural National Conference for LGBTQ people of Korean descent. We’re looking for more volunteers, and you can get in touch with us here! https://www.giveoutday.org/c/GO/a/dariproject

As a long-time supporter of the LGBTQ community and the It Gets Better Project, Rudy’s has partnered with world-renown artist, public speaker, and author Dallas Clayton to create a line of custom tote bags and stickers supporting Coming Out Day and the LGBTQ community. With every purchase of the custom Baggu tote, sticker sheet and Think About Someone You Love booklet (total cost: $21), Rudy’s will donate $5 to the It Gets Better Project. Our collective hope is to inspire people young and old to celebrate their individuality and this special moment.