The romanticization of American heritage is nothing new.

You can find it’s dreamed of and longed for in every art form. Brands of every ilk try to distill its essence down to varying takes of white t-shirts and jeans — using them as a synecdoche for quality and industriousness. (RRL is to Americana as Dr. Bronner's is to a religious undercurrent.) Lana Del Rey explores a different facet of it with every album release, fawning for it like a late lover. Mike Jeffries chased this ideal for his entire tenure at Abercrombie & Fitch. It’s finely woven into the idea of simpler or even purer times. The image conjured in my mind has a leading man — the all-American guy.

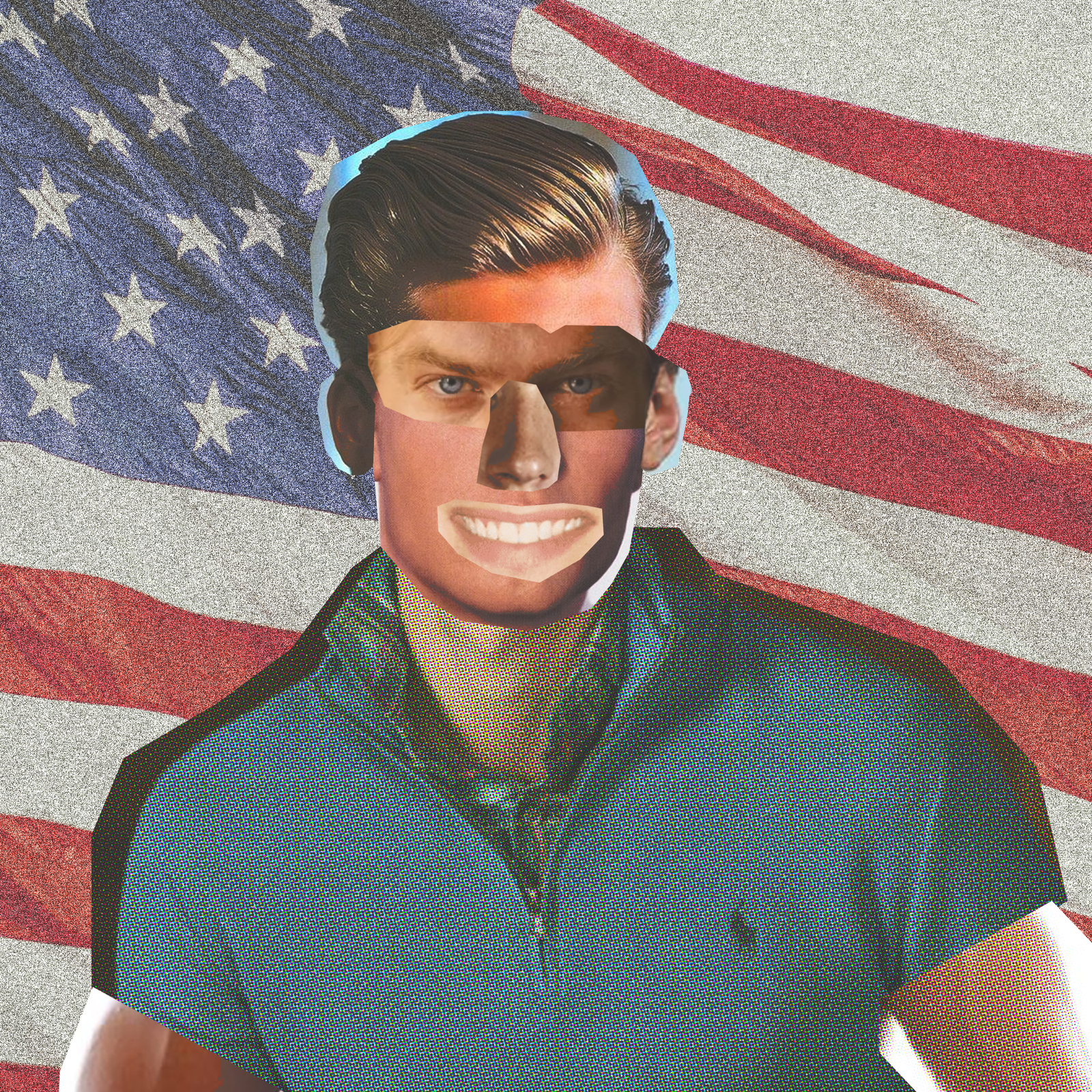

It’s someone who, at a minimum, is six-foot tall. They have one of those taper fades that are done with scissors, rather than an electric buzzer. I’m picturing a specific nose — a steady line graph with a correlation coefficient of exactly 1. I see big straight teeth like a picket fence. A woven bracelet, mud, and abs. They are also as white as the days are long, but browned from outdoor recreation to the color of french fries.

To reiterate, the phrase "all-American" describes a white person.

For any person of color, Americanness cannot really be achieved through naturalization or even birthright."

In order to support this theory, I turned to what should be an impartial robot: Google Images. [I say this partially in jest. Computer science confirms that even AI leans white.] I typed in “all-American guy.” There were 38 image results of what I would consider soft-core pornography before I saw a person of color. As far as I’m concerned, this far down in the search results is the dark web. The problem isn’t or hasn’t ever been that WASP jocks have a nickname. That’s why this story isn’t about the etymology of “beefcake.” This is a story about how Americanness is synonymous with whiteness.

What’s strange about my disconnect to the above image is that, on paper, I couldn’t be any more American. I was born in California. My mother and father are Americans and ultimately, embody the American dream. I live in America and work for an American company. I pay taxes. I vote. Why then, am I (and the millions of others like me) excluded from the mass narrative about Americanness? It reinforces the idea that for any person of color, Americanness cannot really be achieved through naturalization or even birthright. This notion is bolstered anytime someone is told to “go back to their country” — even if that country is the United States.

The idea that you must be white to be American was a prominent discussion point when Minari was excluded from being eligible for Best Picture at the 2020 Golden Globes.

Minari (as well as the critically acclaimed The Farewell and Parasite) were deemed ineligible for Best Picture categories because they contained more than 50% of a non-English language: Korean. Fair, except for when you consider that this rule was ignored wholesale when nominating Inglorious Basterds and Babel — two films that are predominantly non-English — for Best Picture categories. (They won both, by the way.) In The Farewell, Parasite, and Minari’s case, they were the wrong kind of foreign. The romance of the American dream only retains its luster if it’s the right kind of immigrant: one from a European nation. Hard work and industriousness are hot on white guys. On colored skin, it’s slimy and lowly.

The aura of the all-American man comes down to the fetishization of clean-cut mass appeal. What's attractive to the highest number of people? It’s the guy next door. It’s the prom king, but it’s also your childhood bully. He’s supposed to be everyone and no one. For some, he’s what you can aspire to be with enough manual labor and elbow grease. For the rest of us, he is just an unobtainable figment of Bruce Weber’s marketing — as archetypal and made-up as the Manic Pixie Dream Girl or the Magical Black Man. Years of being told that this is the singular ideal to aim for can only let down the people it was never available to. Then again, maybe that was always the point.

READ MORE LIKE THIS