When he was just a student at an all boys boarding school, Michael Dore felt as though he wasn’t developing in the same way as his peers. “People were experiencing something that I wasn’t,” he tells Very Good Light.

In retrospect, Michael acknowledges that during his adolescence, figuring out his sexuality was a challenge. For a while, he questioned whether he was just a late bloomer, but as time went on, Michael still wasn’t sharing the romantic or sexual experiences of his peers. He came to realize he identifies as asexual: a lack of sexual attraction.

SEE ALSO: 4 guys tell their empowering coming out stories

Asexuality is oft a misunderstood orientation. As a sexual orientation, it isn’t addressed in the same way as other marginalized sexualities that are grouped under the LGBTQ+ umbrella. “Society has normalized levels of sexual desire while pathologizing others,” says Karli Cerankowski, a scholar who has conducted extensive studies on asexuality, to Stanford News in 2015. “In a sense, it’s the social model that’s broken, not asexuals.”

One-percent of the population is asexual.

Though their struggles tend to be overlooked and misunderstood, in reality, members of the asexual community face similar struggles to those in the LGBTQ+ community. According to Michael, who is now a volunteer at the Asexuality and Visibility Education Network (AVEN), asexuals have to deal with coming out to their loved ones, the assumption that just having sex will somehow change their sexuality, and are even faced with violence for being who they are.

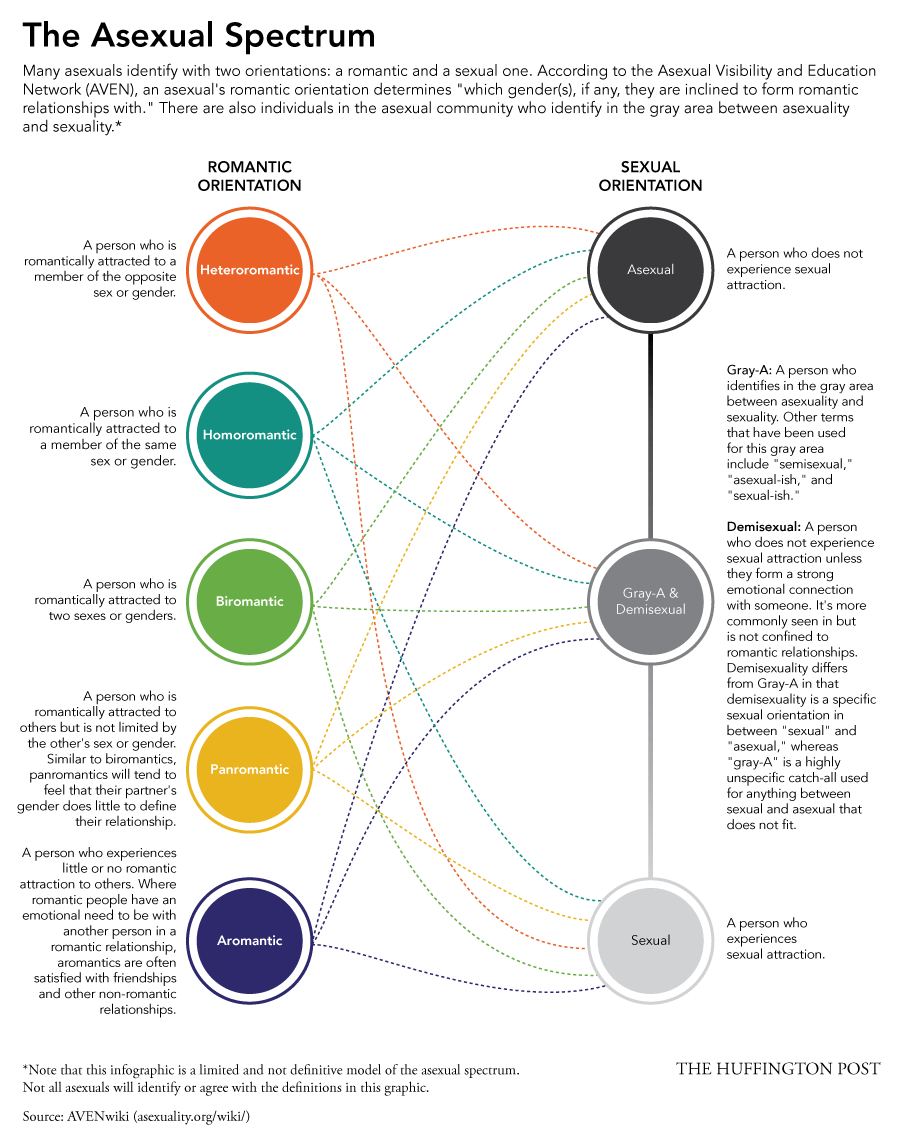

A study conducted in 2004 by Anthony Bogaert, a psychologist and human sexuality expert at Brock University in Ontario, states about 1-percent of the population is asexual. But identifying as asexual isn’t so black and white. In fact, there is an entire spectrum of asexuality. As Michael explains it, some asexuals experience sexual attraction in low doses or if met with certain stimuli. Demisexuals, for example, only experience sexual attraction if they have romantic feelings for someone.

When Michael was figuring out his sexuality, he explains that a major hurdle was the fact that there was no conversation surrounding asexuality. This in turn, made it difficult for him to actually come to terms with what he identified as, or have a concrete label for how he felt. Eventually Michael came out to his friends and family, and now lives proudly as an asexual and aromantic (a person who experiences little to no romantic attraction to another) man. With the work that AVEN, and other organizations are doing to create a stable asexual community, Michael claims things have gotten much better and the asexual community is being highlighted, but “there’s still so much work to be done.”

Below, we spoke to Michael about asexuality, his dating experiences, sexual desires and what he wishes people knew.

Firstly, what is asexuality?

Asexuality is lack of sexual attraction. Everybody has certain people that they’re not sexually attracted to, it’s just for asexual people we find that that covers everybody. It’s not the same thing as celibacy or abstinence. Some asexual people do have sex, and even those who don’t, don’t necessarily regard it as abstinence because they’re not giving up anything. They’re not abstaining from anything because they don’t experience sexual attraction in the first place.

What does the landscape of dating look like for an asexual person?

In some sense the ideal would be for an asexual person to meet and date another asexual person because obviously you’re incompatible if it’s one way, but there are many asexual/sexual relationships, which is great when it works out. Of course, that’s only one area of compatibility though, and the odds are against us because only a small portion of the population is asexual. Often, asexual people do end up finding themselves with people who are not asexual, and as long as like both partners are really clear on their boundaries and what they’re happy with, and as long as they both accept each other’s sexuality there’s no reason that relationships like that can’t work.

Is there an app or anything that can connect asexual people? Like a tinder for asexual people?

Yes. I don’t know whether it’s still active, but there was something called Acebook. We use the word “Ace” as a sort of shorthand for the entire asexual spectrum, including people who are graysexual (a person who doesn’t want sex often) or demi-sexual (a person who does not develop sexual feelings unless they form a strong emotional bond) . I personally identify as aromantic as well as asexual, so I’m not personally looking for a relationship, but some people are so it’s a good place to meet people.

You could be, say, bisexual and heteroromantic, and all these possibilities exist, so we’ve had like every combination you could think of at some point.

What’s the difference between sexual orientation and the asexual spectrum?

When I referred to the asexual spectrum I was really referring to the sexual identity. So, what we define as sexuality is lack of sexual attraction, but there are people who might experience sexual attraction in low doses. Perhaps only infrequently or at a low intensity or perhaps you need certain stimuli, like you need to have an emotional connection to the person before you experience sexual attraction. We call the latter people demisexual. So, it’s sort of a big range, like sexuality is not just an on/off switch.

There’s a big range of attraction, and a separate thing to that is the whole question of romance. So, just like there are sexual orientations –heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, asexual, pansexual – there are corresponding romantic orientations – heteroromantic, homoromantic, biromantic, aromantic, panromantic. They’re just like the sexual orientations except they compose the romantic attraction instead of sexual attraction. These two factors are really quite separate, so you could be any combination. You could be asexual and heteroromantic or aromantic, or for that matter you don’t have to be asexual at all. You could be, say, bisexual and heteroromantic, and all these possibilities exist, so we’ve had like every combination you could think of at some point.

How do you know that you’re asexual?

I can only speak from experience. I grew up in an all male school and at a time when all my peers suddenly became very interested in the opposite sex it was just something I couldn’t understand. It was like a different language, and I didn’t identify as anything at that point partly because asexuality wasn’t really well known back then, but also I also didn’t want to label myself when I could just be a late bloomer or something. As the years went by it was very clear that other people were experiencing something that I wasn’t, and the term asexual just fit me. People would ask me are you straight or gay, and I was like ‘No, I’m actually asexual I just don’t experience sexual attraction to anybody.’

What I would tell people is just not to worry about it too much. If the word asexual seems to fit you at the moment, and that you don’t seem to be experiencing something that your peers are in regards to sexual attraction then feel free to use the word asexual. It’s not unusable. You can decide in a couple of years that this label no longer fits you. It’s just whatever makes sense to you at the moment in time.

Do people who identify as asexual have a process that’s similar to coming out? How did your parents or siblings react to being told that you’re asexual?

Yes, very much so. In many ways it can be very difficult to come out because for your family and those you’re closest to it’s a difficult thing to talk about. It’s very intimate. Parents just assume that their children are going to be straight like most of the population, and it can be extremely difficult because they’re exactly the people you don’t want to disappoint. Even if your parents are not homophobic or anything they might just still expect that their child is going to be straight. For many people who haven’t even heard of asexual and asexuality it can be a difficult thing because in some areas you find people who think asexuality is just a cover for being gay. Especially in very homophobic areas. Often you do get that, and people think well if you’re not into one you must be into the other, so it can be very very difficult to come out because there can be a lot of judgment.

In your personal experience, what’s been the most difficult obstacle that has come out of identifying as asexual?

I think it’s just getting over that initial hurdle of first of all coming out to your friends and then coming out to family and parents. You get all sorts of reactions like ‘it’s just some phase you’re going through’ or ‘it’s just something you made up’ and people have a lifetime of invalidation sometimes. They feel something but they’re told they’re not supposed to feel that way and it can be a very difficult internal hurdle to get over. As far as external hurdles it depends so much on how accepting friends and family are, but I tend to find it’s more in the homophobic areas where we expect everybody to be straight — that can be very difficult for an asexual person, even though asexuality is not the same thing as being gay or bi, but a lot of the issues are still there.

In some of the research I’ve done, asexual people like to be defined under the umbrella of LGBTQ+, do you find that to be true?

Absolutely. We see ourselves as a sexual minority and so we fit in that regard. A lot of the experiences asexual people have are actually very similar to what people in the LGBTQ+ community go through. It’s relevant to note that a lot of asexual people are outside of the gender binary even though sexuality and gender are two different things, we have a high proportion of trans people in our community, and a very high proportion of non-binary people, and so we see ourselves as very close to the LGBTQ+ community, and we have a lot of overlapping issues. Another overlapping issue is that asexual people can get homophobic abuse. Asexuality and being gay aren’t the same thing, often people really don’t understand the difference. They think if you’re not into one you must be into the other. But it’s up to the individual. If an asexual person doesn’t feel like they’re part of the LGBTQ+ community then that’s okay. As a community, and in terms of disability efforts we do align ourselves quite closely with the LGBTQ+ community.

Do you feel like members form the asexual community suffer from similar kinds of violence as people in the LGBTQ+ community?

Yes. I think that there’s a very strong element of truth in that. First in that often the distinction between asexuality and being gay is not understood, so you if you’re going to get beaten up as a guy for not being into women, then that’s sort of the same if you’re gay or asexual. I’ve had that sort of abuse personally. The other thing is there can be issues around coercion and consent, and I think this impacts on women more than men, though it could happen to anybody, and sometimes there’s the idea that if an asexual person sleeps with someone their sexuality will be fixed somehow.

Is there any advice you would give asexual people who are struggling to find themselves and define their identities?

The first thing is to find a supportive community whether online or offline. I would recommend joining forums that have a space full of other asexual people. Another thing is if you live near an offline community, like on a campus where generally a lot of Pride groups will provide a space for the asexual community, it’s important to seek out people and discuss things.