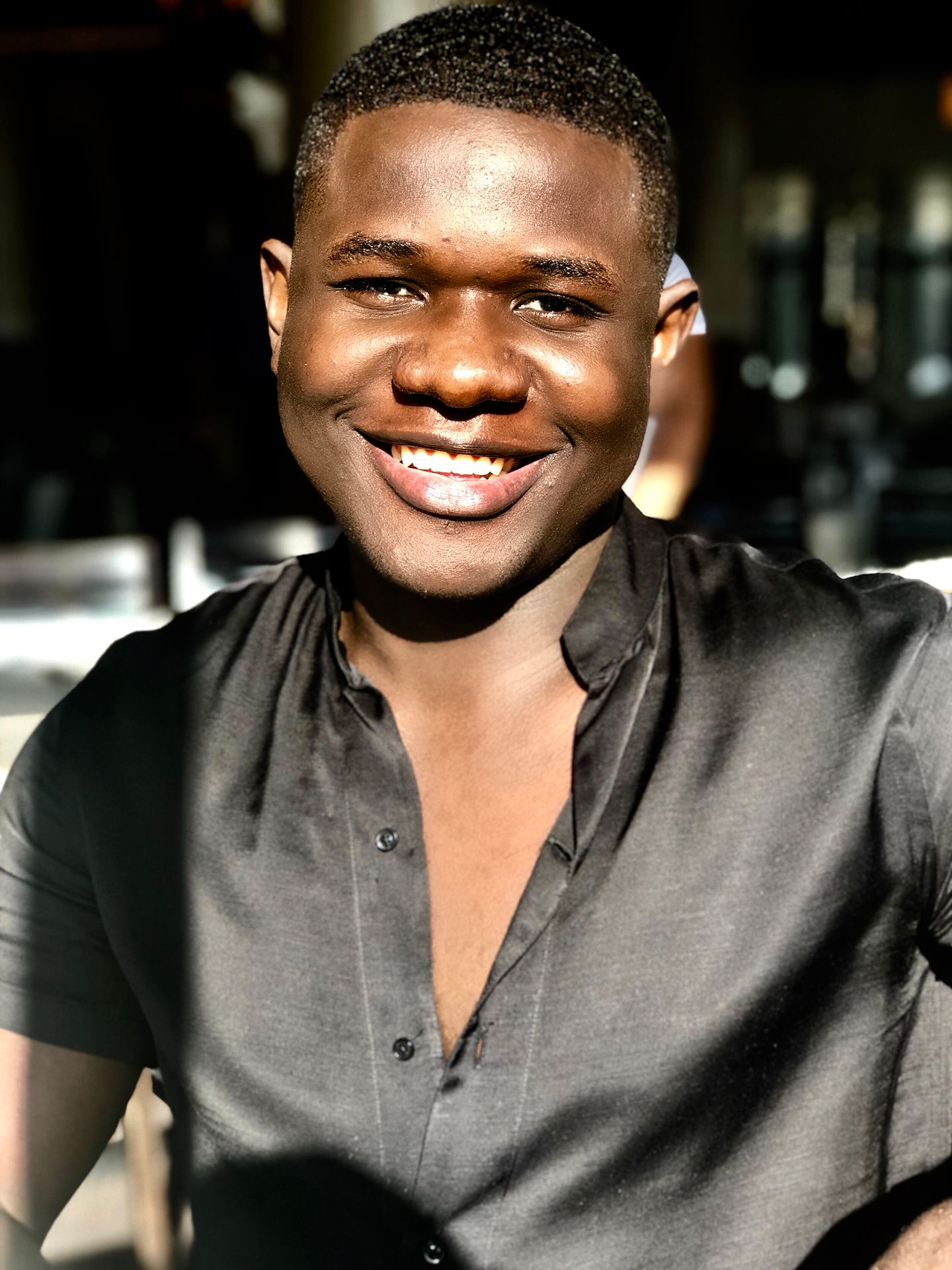

This time last year, Richard Akuson, 25, seemed to have it all.

In his hometown of Abuja, Nigeria, he was not only the founder of a boutique PR agency called The PR Boy but running one of the most controversial websites in the country – A Nasty Boy – which was all about redefining masculinity in Nigeria. The groundbreaking magazine, which wasn’t marketed as outwardly queer (being homosexual is punishable by law), became an overnight international sensation, covered in places like the BBC, CNN, among others.

“[A Nasty Boy] chooses to paint otherness as nothing but a beautiful time,” described i-D magazine.

Today, Richard is couch surfing.

SEE ALSO: We need to acknowledge how coming out is still a privilege

Now a candidate for sexual orientation and political opinion asylum, he lives in Arlington, Virginia with a bank account that’s empty.

In the summer of last year, Richard was the target of a brutal attack. His public profile as the founder of a publication that celebrated queerness was basis enough for a group of men to physically abuse him. They lured him and eventually outed him to his family. In Nigeria, where being gay is punishable by law, being visibly queer is life-threatening. Following the attack, Richard felt he had no option but to flee, hoping to find refuge as an asylee in the U.S.

As a result, A Nasty Boy, once a beacon of hope for the Nigerian LGBTQ+ community, is now a thing of the past.

“What really pushed me to start A Nasty Boy were the falsehoods propagated in mainstream media about LGBTQ people,” says Richard.

They proceeded to strip, beat, and poke his anus with sticks.

Richard’s height towers over but his stature is juxtaposed by his soft-spoken, whisper-like British accented voice. He’s shy but affable and it’s evident that he speaks thoughtfully with every one of his words.

Today, we’re sitting in the lobby of his friend’s luxury apartment building: an expansive structure of marble and over-tufted sofas, decked out with private conference rooms and lounging areas. The building is something out of Architectural Digest – it’s pristine, it’s beautiful. It’s also temporary.

Within the Nigerian context, the fact that A Nasty Boy was able to attain international success is groundbreaking. In 2014, former Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan passed the Same-Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Bill (SSMPA) into law, effectively criminalizing members of the LGBTQ+ community. According to a 2016 Human Rights Watch report on the effects of SSMPA, the law bans any form of cohabitation between same sex partners, as well as any public display of affection between them.

So much about A Nasty Boy had to do with normalizing and humanizing our lived experiences as gay people.

Further, “it imposes a 10-year prison sentence on anyone who ‘registers, operates or participates in gay clubs, societies and organizations’ or ‘supports’ the activities of such organizations.” In the 12 northern states of Nigeria, where Shari’a law is practiced, homosexuality is punishable by death.

Graeme Reid, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) rights director at Human Rights Watch, commented in the report that the law was completely debilitating to this already marginalized group. It is within this environment that Richard decided to start his publication.

“I felt an obligation to counteract that with alternative and positive narratives,” Richard says of starting A Nasty Boy. Despite the “fear of being discovered or outed” and the persecution that comes along with that, he says “I felt like they were important stories to tell … they were absolutely necessary.”

Besides being victim to criminalization, the Nigerian queer community is also faced with the overwhelming fact that their society supports their persecution. In a 2016 Global Attitudes Survey on LGBTI People by the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Trans and Intersex Association, in Nigeria, 59% of respondents said that being LGBTI should be regarded as a crime, and 62% said same sex-marriage shouldn’t be legal.

A Nasty Boy sought to bring joy – and much needed light – to the Nigerian LGBTQ+ community.

Through its stories, A Nasty Boy sought to celebrate queerness with stories ranging from fashion and beauty, to personal essay and more.

“The Nigerian media engages with the notion of homosexuality from a sexualized point of view,” Richard say. “They see the act before they see the person. So much about A Nasty Boy had to do with normalizing and humanizing our lived experiences as gay people.” The very act of being seen was one that was an utter act of defiance.

Though controversial, Richard felt that the stories he published were making strides towards at least opening up conversations surrounding sexuality; activism through fashion, beauty, identity was central.

“I remember stories that we shot with (male) models wearing makeup and dresses,” Richard recalls. “Those sparked meaningful conversations around gender norms and masculinity.” The stories allowed the Nigerian community to consider the various facets of sexuality in a context where that was almost entirely shied away from.

While A Nasty Boy pushed boundaries by proudly expressing the experiences of the queer Nigerian community, there were clear risks in doing so. Richard acknowledges he started the publication from a place of privilege: “I felt like I had enough safety to have such a publication,” he explains. “As a lawyer, I felt like I understood the law enough to know where the limits were and how far the publication could push.”

But the attack proved otherwise.

The day he was ambushed, four men accused him of “spreading a gay agenda.” They forced him to unlock his phone and saw its contents as proof of his homosexuality. They proceeded to strip, beat, and poke his anus with sticks. The attackers went so far as to take pictures of Richard beaten and crying in order to, as Richard describes it, “memorialize the violence and inhumanity of their triumph over me.”

Following the attack, Richard says he hoped things could go back to normal. But he realized that he “didn’t know what normal felt like anymore.”

He fidgets uncomfortably with his cup of tea as he thinks back to the day he was attacked. “I couldn’t stay,” he says. “I didn’t feel safe – in fact, I felt alien.” Almost a year later, he still lives in fear that he could be attacked again.

By being at the receiving end of the violence of homophobia, Richard realized he couldn’t continue the publication. “I lost the certainty of safety and security that I had, which was at the core of who I was, and at the core of A Nasty Boy.”

In Nigeria, where being gay is punishable by law, being visibly queer is life-threatening.

Omolara Oriya, a director at the Initiative for Equal Rights (TIERS), told the Guardian in 2018 that the nature of crimes against the LGBTQ+ community, which TIERS has been documenting since 2015, has changed in recent years. “Violence is very common… but from 2016-17 we saw a decrease in violent acts,” she says. “What has risen significantly is extortion, blackmail, infringement of rights to assembly, and police malpractice.”

Mass arrests based on the presumption that the people gathering are gay is fairly common in Nigeria. In 2017, 53 men were arrested for attending what the police claimed to be a “gay wedding” in Zaria. That same year another 40 men were arrested at a hotel in Lagos for reportedly “performing homosexual acts.” And in 2018, police raided a birthday party in Lagos and arrested 57 men for “homosexual activity.”

While coming to the U.S. afforded Richard the ability to be himself and escape the criminalization that so many gay men are subject to in his home country, it has put an end to the “rosy and beautiful and almost perfect” life he’s always known. Coming stateside has been sobering.

“Denounce being gay. Repent. Give my life to Christ. Give up my ungodly desires. And go back.”

“I’ve been here since July,” he tells me. “I’ve not worked. I’ve not earned. I’m squatting right now with my friends. I don’t have anywhere to go.”

Upon arriving in the U.S., Richard had his own place in Foggy Bottom, a quarter in Washington D.C. After only a few months with his savings spent on finding a lawyer for his asylum case, he had nothing left.

“Just the other day, when I thought I was at my lowest point I called my mother begging her for money,” Richard says. “She was like, ‘Your father said this was going to happen and we should not encourage it. You know what to do if you really want our help.'”

When asked what his mother wants him to do, Richard responds almost robotically, as if the order has been battered into his head: “Denounce being gay. Repent. Give my life to Christ. Give up my ungodly desires. And go back.”

The day after his attack, Richard was anonymously outed to his parents. This has caused him to be estranged from his family, particularly from his father whom he’s spoken with only once since the attack. With no other viable option to earn money until he can legally work, Richard has set up a GoFundMe for financial support.

“For the first time my life is like a balloon on water, just floating with no sense of direction,” he says. “It’s a struggle everyday finding motivation to survive.”

Despite the odds stacked against him, there is an unmistakable confidence in the way Richard speaks about his achievements and endeavors, a trait he grants to his Nigerian culture and the way he was brought up. “There is a sense of pride that comes with the knowledge that you’re Nigerian, and so it affects how you approach life,” he says, beaming. “It’s something that has inspired so many of the things that I’ve done.”

When asked if he feels as though his country let him down, after a long pause, tears collect in his eyes. Staring down at his paper cup of tea, wiping his face, collects himself. “A part of me still holds on to the dream Nigeria could be a safe haven for LGBTQ people like me someday,” he says.

He takes a deep breath, and continues: “Part of me still holds on to the beautiful memories, the family, the friends, and the life that I left behind… but at the same time I am heartbroken when I remember all that has happened to me there.”

At his lowest moments, he questions it all. “I regret ever starting A Nasty Boy,” Richard says. “I would give anything to have my life back,” he utters, fighting back tears. But then he realizes the bigger mission, and he comes back: “This experience has been transformational. It has taught me a great deal about myself, and about life.”

Then there are new experiences – like freedom to just be – that have been transformative. For the first time in his life, Richard says, he can freely and openly be a gay man.

“I’ve met more gay men in the months I’ve been here than I have in my entire life,” he says.

He’s been dating, and, like any other millennial, swiping on Tinder. “I don’t take for granted being able to walk down the street and hold someone’s hand,” he says. “Knowing that I could kiss someone anywhere I want is…” His voice trails off, and his face lights up, smiling, almost as if he’s reminiscing sharing the most magical kiss.

Despite everything he’s been though, Richard is proud. He’s a proud gay man, and he’s a proud Nigerian man. Even now, he refuses to believe those identities are mutually exclusive.

To support Richard, donate to his GoFundMe here.

UPDATE: A month after reporting this story, we reached out to Richard to see what he is up to. He told us he’s no longer couch-surfing as he just found two new clients for his PR business. He tells us this via email: “Because of this new development, I’m no longer couch-surfing; I’ve found an apartment. And even though I’m still not where I used to be in terms of financial security and safety, I believe my financial reality isn’t as stark as it was a month ago. I believe it’d be quite disingenuous of me if I didn’t mention this.”