Like many immigrants, my parents moved to America out of necessity. South Korea wasn’t like it is today with its blinding lights, massive pop culture appeal, and multi-trillion dollar beauty industry.

It was the 1980's, a time when the country was reckoning with its own stance on democracy, still healing its wounds from a war with the north and finding its way out of mass poverty.

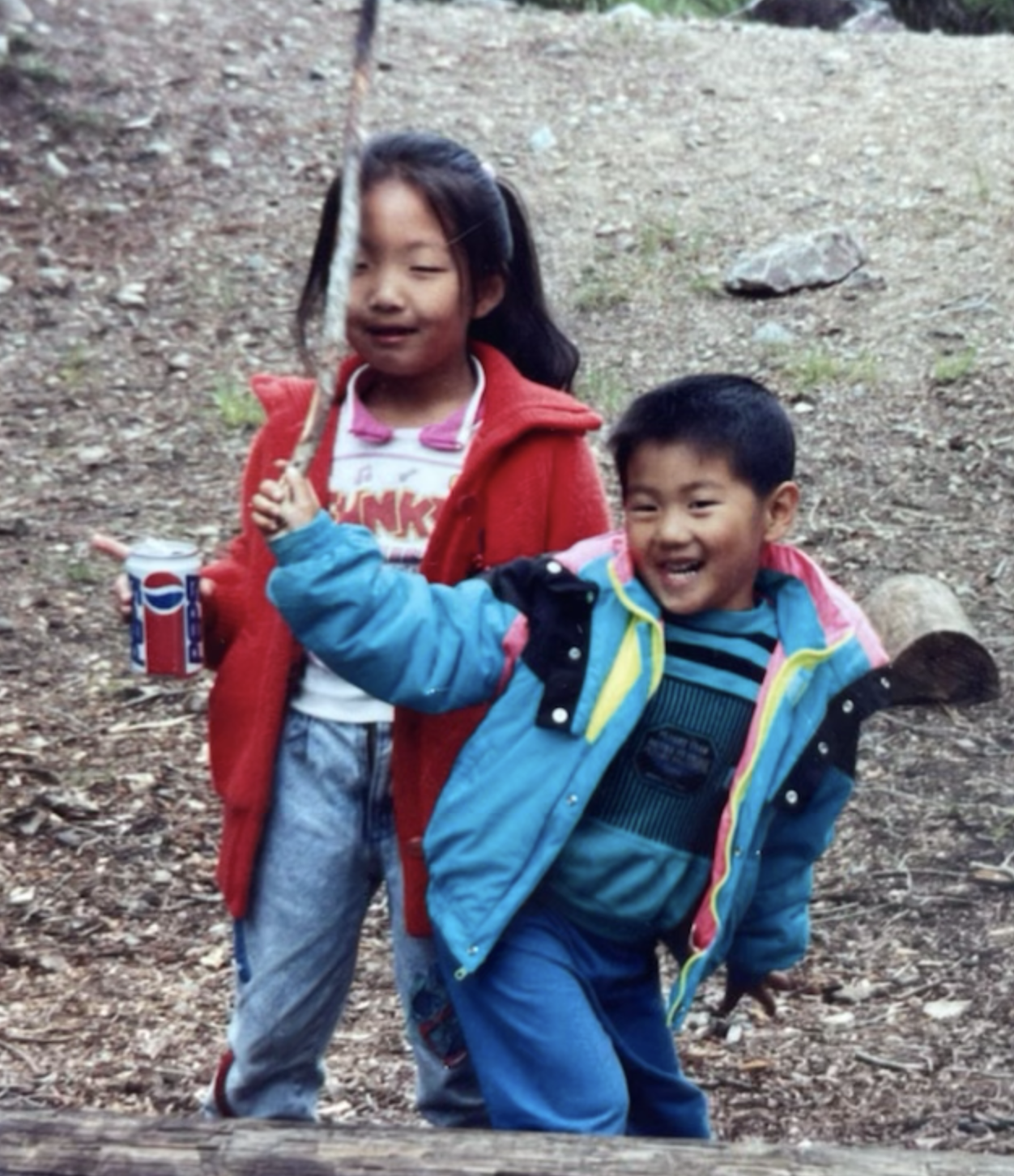

And so when an opportunity came for them to leave, they packed their bags for the south side of Colorado Springs, CO, where they worked manual labor jobs, ones that were respectable and helped put food on the table. Umma was pregnant with me while raising a 3-year-old girl named Jamie. She worked at a factory, assembling electronic parts, and did so until her water broke and a baby boy (me!) was birthed. Meanwhile, Appa worked as a janitor with my older uncle, where both would clean out office buildings, the only job where you didn’t need a firm grasp of the English language. “You didn’t need so much communication: sweep, mop, clean, put your head down, work.”

They’d save a week’s worth of earnings and send it back to South Korea, where my grandmother, grandfather, uncles, and aunts lived.

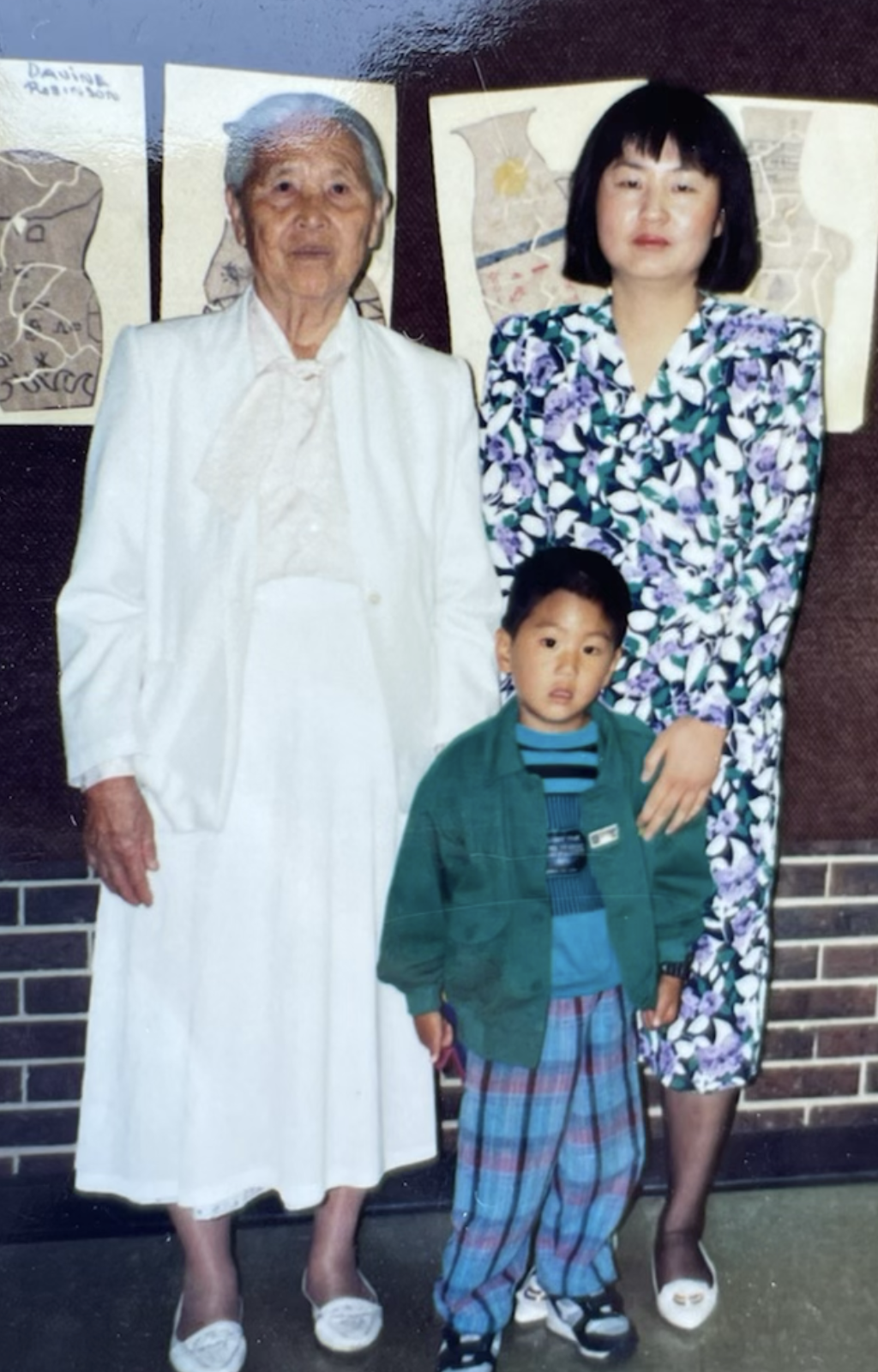

Years later, Appa and Umma moved away from the two-story house they shared with their siblings and into an apartment complex. There, my sister and I shared a two-bedroom apartment with our maternal grandmother, wae halmoni (maternal grandmother). She occupied the living room’s floor on an electric mat as my sister and I shared a queen-sized bed that took over three-quarters of our tiny room. It may have been claustrophobic for any adult, but for two spritely children, it was magic.

When I was in the second grade, my parents put their life savings into a convenience store and, eventually the liquor store next to it. The liquor store was my parents’ American Dream, and they named it Family’s Liquor Store, a nod to how much family meant to them. Liquor stores within the Korean American society at large are considered golden — a business that could thrive and put children to college, fund family members coming to America, and a small savings account.

It’s why it was worth it to work from morning to past midnight stocking the Bud Light and Hennessey; brave the dangers of the occasional problematic customer; work the merciless seven-day week. Neither of my parents had a Plan B — this was it: working away to send their kids to college, providing for their futures. This was their American Dream.

One day while I was sitting in the liquor store office, my elementary school principal walked in. “Junyoung ah,” my appa called me by my Korean name. “Your principal is here. Say hello!” In a panic, I fled to the restroom and closed the door. “Where is he?” umma asked.

“He must be using the bathroom,” they told my principal as he paid for a bottle of wine. “Have a good night!”

I waited for my principal to leave, tiptoeing out of the bathroom to ensure he was, indeed, gone. I’d held my breath so that he wouldn’t see me — and if I did it long enough, perhaps I’d disappear. As my parents walked into the office, they looked over at me, flinching.

“Why didn’t you come out?”

In all honesty, I hoped they wouldn’t know that I was none but rosy-cheeked, a bit embarrassed that our family business was a store that sold liquor to customers on the south side of town. My eyes fixated on the carpet, I walked off into the back of the store near the buzzing refrigerators, hoping my parents wouldn’t sense the shame that was rising in me like the heat on that September night.

But I felt they did.

They didn’t show it, but I knew how hurt they must have been, feeling judged and condemned by their only son. While they had pursued the American Dream, fulfilling their purpose of providing for their family, their feet swelling through their shoes, their backs sinking into the Earth from the boxes they carried, their fingers calloused from the heavy lifting, it was me who would break their hearts.

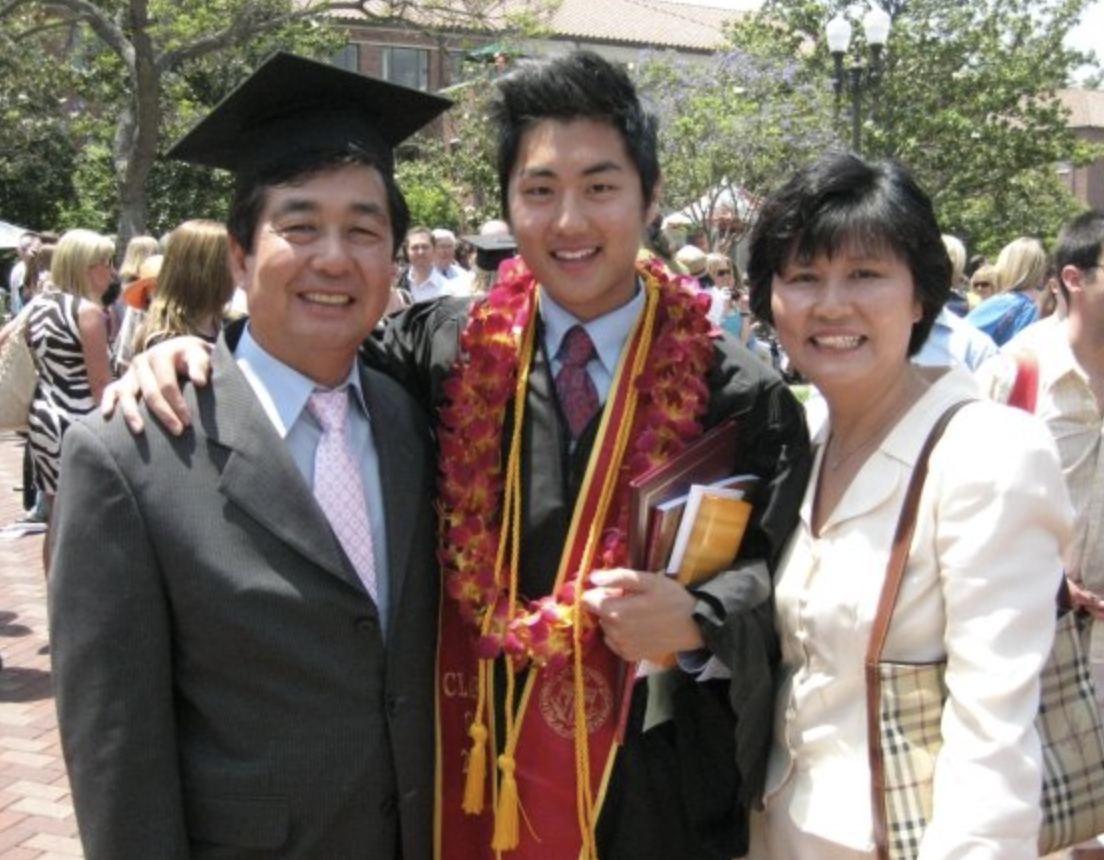

I hope it wasn’t in vain. While their son was privileged enough to go to an elite college on the west coast and live his twenties in New York City, they were the ones who were left behind — still working, stocking beers, pressing buttons on a register, hoping one day their son would see them for who they were: humble, hard-working, dignified first-generation Americans who were proud of themselves.

Years later, I realized just how instrumental their liquor store dreams were in building a foundation for me to become my own entrepreneur. Everything I’ve learned about business came from them. And it is because of them that I was confident enough to start my own business, good light cosmetics, a brand that’s now over a year into its existence.

While my brand heads to Ulta Beauty in over 750+ stores come Monday, July 18th, I can’t help but pay homage to my parents, their liquor store dreams, and that humble, consistent hustle that allowed me to have the audacity to pursue my own.

It was only through them that I could even imagine going into a major retailer like Ulta, and it’s because of them that I don’t fear the unknown. After all, it is my parents – two immigrants who barely spoke English, a couple of dollars in their pockets – who dared to dream. And it’s because of them that I have the opportunity to dream as well.

I hope that when my parents peruse the shelves of Ulta and spot good light, they know that this is their legacy as well. This is their life’s journey for other Americans to witness. And my greatest hope is that they feel seen. They are celebrated.

They are the American dream – and this is also their moment.

READ MORE LIKE THIS